In early April 2019, renowned Travel Writer Simon Parker and Professional Travel Photographer Ben Read visited Nepal for the very first time.

Their brief was to produce an article about Nepal away from the main tourist trails for the prestigious ATLAS IN-FLIGHT MAGAZINE for ETIHAD AIRWAYS, one of the world’s leading, luxury airlines. The Atlas Magazine is estimated to be read by up to 20 million people!

SNOW CAT TRAVEL were chosen by Etihad Airways to design a tour of Nepal for Simon and Ben, as well as take care of all the arrangements in Nepal for them too.

This article has now been published in the June 2019 Atlas by Etihad magazine, from which we have reproduced below…….enjoy!

THE HIDDEN SIDE OF NEPAL

The so-called Roof of the World is more than just a high-altitude haven for backpackers on a budget. Atlas shuns the Himalayan tourist trail for the unsung Middle Hills to experience Nepal with the Nepalese

Simon Parker, photos by Ben Read | June 2019

“People come to Nepal and get what we call ‘altitude fever’,”yelled my rafting guide, Durga, as we sloshed over the warm, soupy and very loud rapids of the Trishuli River, around 75km west of Kathmandu. “Even if they aren’t going to climb Everest, they just want to go up six or seven thousand feet so they can show off to their friends back home,” he bellowed, as the boat barged between boulders the size of hatchbacks, beneath long, sun-washed prayer flags flying high above the river. “Why would you spend two weeks in the mountains with thousands of other Westerners when we have all of this right here? Nepal is more than the Himalayas.”

An elderly man walks the streets of Kathmandu-Ben Read Photography

Why indeed? Except for the occasional fisherman netting sprats from the bank and farmers panning for gold in the calmer shallows, we had the whole river pretty much to ourselves. Hurtling downstream, we twisted and turned. Tiny sand martins snapped at gnats flitting above our helmets as our ridiculous, banana-yellow rubber raft bounced and lolloped past mothers lathering clothes in foamy soapsuds, their toddlers erupting into fits of giggles as we passed. Shrouded beneath a haze of wispy cloud and milky smog, the Himalayas were less than 100km to the north. Most of the tourists who passed through Tribhuvan Airport that week were either already in Lukla, the gateway to Everest Base Camp, or on the way. It seemed I was the only one who wasn’t.

Instead, I was in the Kathmandu Valley, Nepal’s so-called Middle Hills, the little-visited region of mostly humpbacked, mogul-like foothills between the lowlands of northern India and the world’s highest mountain range. It was here, I was told, that I would find the most tangible signs of Nepal’s tilt away from tourism aimed at backpackers to something a little bit more upmarket.

Travelling here has always been arduous and uncomfortable – and, after a bumpy, unpredictable three-hour drive from Kathmandu, I can attest that’s still more or less the case. Still, change is fast afoot: in the run-up to Visit Nepal 2020, a push to attract two million visitors next year, ambitious engineering projects are underway throughout the Kathmandu Valley, including an additional 170km highway linking the capital and Tibet. Tourism fell off by a third after the devastating earthquake of 2015, but has since grown to overmatch pre-quake levels. Just as well: it’s the country’s largest earner. Now a new wave of midrange hotels is opening its doors while many older properties are being revamped. Could this small, landlocked country shake off the old hippie-trail image of backpacker guesthouses and $1 dorm rooms and move towards slightly higher-end holidaying?

Early signs were promising. After a day of rafting on the Trishuli, I dried out at The Famous Farm, one of the Nuwakot region’s best guesthouses, which, anticipating more visitors, was eagerly adding a further six rooms to its current 14. Exhausted, but in awe of its balmy, hillside microclimate, I supped an ice-cold lager as the warm scent of bougainvillea and busy Lizzies wafted between cobbled courtyards of grape vines and pink roses. As a rust-coloured sun sank into the Nuwakot Valley, I refuelled with a bowl of spicy lentil dahl, mango pickle, egg curry and spring onions sautéed with runner beans and cauliflower – all grown in the hotel’s organic garden. Crisp, white sheets and a warm shower made the place even more inviting; not a single sleeping bag in sight. Adventure at the cost of comfort? Not here; I had my best sleep in months.

Even so, in its current state, this region of Nepal is far from the finished article. The following day, I went to Nuwakot’s 18th-century palace, an ornate, red-brick citadel perched on a hilltop speckled with banyan trees. Like much of Nepal, it’s currently undergoing a meticulous, post-quake rebuild but, despite deep and jagged lesions, it remains a robust and imposing structure formed of wide slate eaves and wooden struts.

“After the earthquake hit, it was tough for us, but now it’s an exciting time for everyone,” said my guide, Dambar. “These days, tourists can move between guesthouses and do things along the way. Everything is moving in the right direction. But it will take time.”

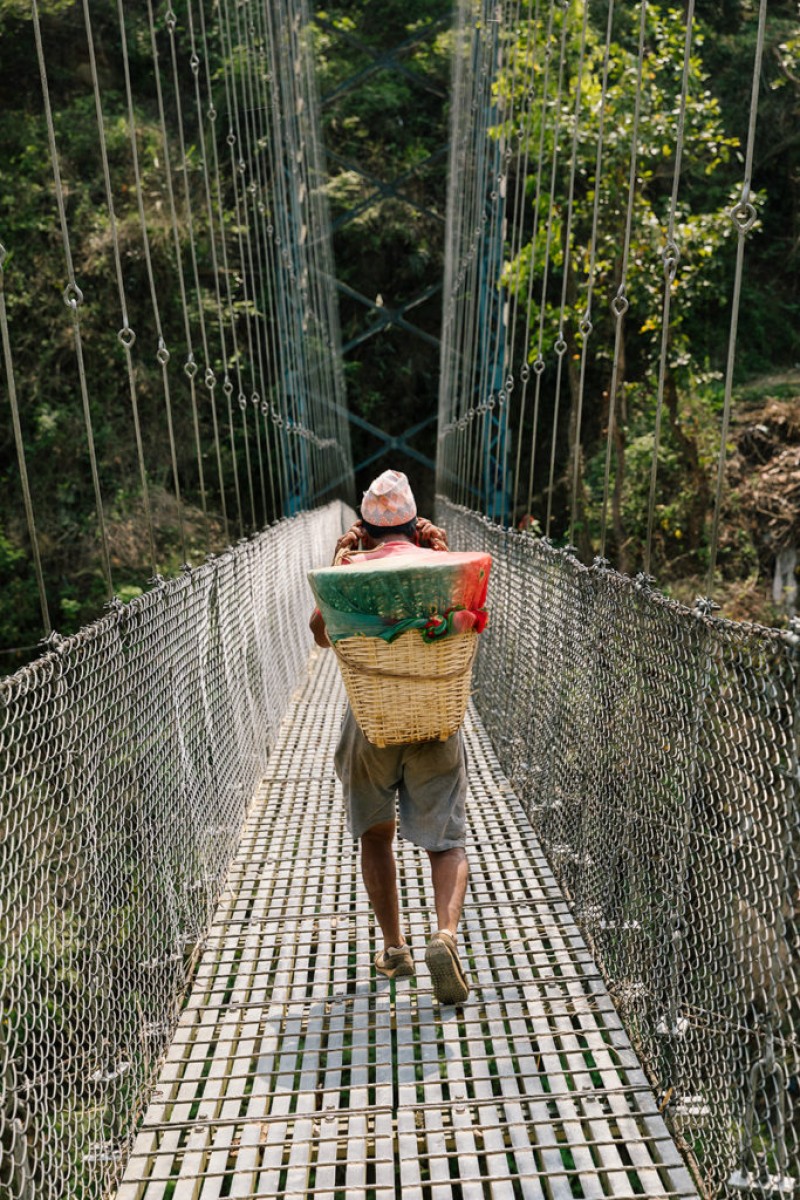

He’s right: as far as tourism is concerned, Nuwakot is very much a work in progress. As I found again that day, road journeys are often white-knuckle, bumpy affairs, and domestic flights linking small towns and cities are regularly cancelled due to bad weather. But despite its challenges, visitors with a sense of adventure and a lust for the road less travelled will be met with staggeringly vibrant and verdant landscapes. It felt as though I was exploring a corner of the Indian subcontinent that had slipped, wonderfully, under the radar. Puddled rice paddies jutted out from steeply pitched emerald hillsides and thickets of bushy wild cannabis plants, with broad leaves the size of dinner plates, beside small organic plantations of cabbages the breadth of beach balls. I’d share smiles with Gurkhas clad in pristine camouflage fatigues as they manned sleepy military checkpoints on my way to Pokhara, Nepal’s second city.

Adventure tourism, like in much of the country, is the big pull in the Middle Hills. That afternoon, I strapped myself to a pilot wearing a nylon paraglider and threw caution (and myself) to the wind. As we soared to 1,500m on warm thermals beside vast, slender-billed vultures, I caught a glimpse of Annapurna, hogging the snow-lined northern horizon with its blunt, 8,091m peak, grand and imposing, yet satisfyingly just out of reach. Paragliding is a boom industry here: tourists get to feel the breezy peace of flight; Nepali pilots earn a living in US dollars. At ground level, Annapurna is undeniably chintzy, with a lakeside strip of neon-signed bars and stores peddling counterfeit climbing gear. But from the bird’s-eye vantage of a paraglider, the glassy water reflected a kaleidoscope of a hundred or more pastel-coloured parafoils, bordered by lush slopes cloaked in jungle.

“There’s three, and there’s a fourth,” said my pilot, pointing out a handful of three- or four-star hotels under construction. “Everything is quickly changing,” he told me, as we plunged towards the lake.

One of the most surprising things about exploring this region came in the simple joy of just ambling around the small towns and cities of the Kathmandu Valley. Hilltop settlement Bandipur’s quaint pedestrianised centre has a South Asian-meets-European vibe that reminded me of the former French colonial settlement of Puducherry, India. Outdoor dining, picnics and sundowners seemed very much the cultural norm.

Bhaktapur, just half an hour from Kathmandu’s airport, was also a revelation to explore on foot. I would implore every tourist heading to the Himalayas to spend at least a night here in extended transit. Its tightly packed alleyways lead to artists’ studios and cafes before opening up into grand bricked squares. I lost several hours there, just mooching between sunny courtyards and Hindu shrines draped in garlands of tangerine marigolds.

It’s amazing these wonderful parts of Nepal remain so little visited, but perhaps the biggest loss is that so few tourists bother to give Kathmandu much time before flying northwards to the mountains. Granted, the capital appears sprawling, grey and messy from above, and a criss-cross mesh of bamboo scaffolding still surrounds most of the city’s earthquake-hit major landmarks. But despite the obvious infrastructural turmoil, the pockets of cultural detail I experienced here were as arresting as anything I’ve ever seen in South Asia. It was here, again, that I experienced a sensation I’d had throughout my trip: I felt as though I was sharing Nepal with the Nepalese, not an endless procession of fellow tourists. “In Nepalese culture, visitors are sacred,” said Dambar. “We want to share our country with people from around the world.”

With dignity and pride, he might have added, whatever the challenges; a point made tenderly clear on my last day in Nepal. At the capital’s Hindu cremation temple, Pashupatinath – similar to Varanasi in India, but smaller-scale – I stood beside wonky bell towers and out-of-kilter Sanskrit-engraved facades. In the immediate aftermath of the 2015 earthquake, this was the epicentre of Nepal’s nationwide grief. But on the drizzly morning I visited just one amber pyre was ablaze as a family of 50 devotees mourned the death of a loved one, their wails echoing among locals and foreigners alike. I have never witnessed a moment so intensely intimate yet so openly public.

“Death is a part of all of our lives,” muttered a souvenir coin seller beside me, as the sound of camera shutters fell eerily, but respectfully, silent, and the words of Durga, days before, calmly returned to mind. More than the Himalayas, indeed.

Simon Parker’s trip was organised by Snow Cat Travel, an exclusive tour operator that arranges private, bespoke tours and treks of Nepal and Bhutan. For enquiries email [email protected]